A break in the clouds allows the morning sun to warm the remnants of a ravaged deer carcass. Bits, pieces, and blood are scattered across a thawing spring landscape. Coyote, fox, marten and raven fight for their share.

High above on the range’s rocky wind swept crest Gulo gulo; skunk bear; devil of the north; big-ass weasel; the glutton, strides across the wind-hardened snow. Prevailing winds sucked across the flat potato fields and sagebrush desert of the Snake River Plain collide with the massive 30,000 ft displacement of the Teton Fault. The rising air mass carries with it the stench of decaying herbivore. With nostrils full of hunger, the wolverine, sniffs at the up-canyon wind.

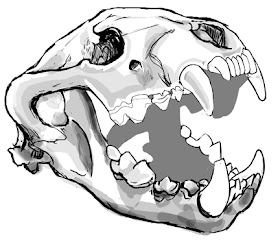

Drawing of a Wolverine Skull by Ann Sue Ong

There it is — the tantalizing stench of decaying ungulate: subsistence, dinner, survival. The five-toed mountain mustelid descends the sastrugi and barren wind swept rock to krummholz then scattered stands of whitebark pine and sub-alpine fir. Lower down the mid-sized carnivore navigates a forest of Engelmann spruce, Douglas-fir and Lodgepole pine. With five-inch paws below 30-pounds of muscle and fur the master of the winter wilderness lopes easily across the softening, unconsolidated snow.

The glutton crosses a series of other critter tracks. Stop and sniff — canine, one of the smaller kind, only a few. The wolverine continues: determined, unafraid, and most of all, hungry.

Wolverine and Ski Tracks along Berry Creek

Grand Teton National Park

Grand Teton National Park

It was the best job I ever had: Wolverine Field Biologist. Off and on for six winters I got paid to roam the mountains and wilderness of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem learning what could be learned about the elusive and little understood carnivore.

During the winters of 1998 and 1999 wolverine expert Jeff Copeland and members of the 4-H Club in Alta, Wyoming had captured and marked two wolverines they named Annie and Danny. To capture wolverines wildlife biologists construct box traps or mini log cabins with a trap door for a lid. To keep the feisty creatures from chewing their way out the logs have to be at least a foot thick. The neck muscles of a wolverine are nearly as large as their heads — collars don’t stay on so well. Researchers, instead, surgically implant radio transmitters in their abdomens.

Box Trap in Darby Canyon, Targhee National Forest

About once a week mountain pilot extraordinaire Gary Lust of Mountain Air Research of Driggs Idaho, flew his small 185 Cessna single prop plane equipped with a radio telemetry receiver, across the Teton Range and recorded approximate GPS locations for Annie and Danny. That is until Danny died.

High in the South Fork of Cascade Canyon, under 20 feet of avalanche debris, Danny lay dead. Wolverines, especially males, are territorial. An adult male can have a home range size of up to 500 square miles: nearly the size of the Teton Range. Before he was killed in an avalanche Danny had been the lone dominant male for most of the Jedediah Smith Wilderness and Grand Teton National Park.

Rachel Wigglesworth and Danny

Cascade Canyon, Grand Teton National Park

In January of 2002 I was filling in as the Chief Winter Guide for Exum when I received a phone call from a Rachel Wigglesworth, a wildlife biologist I’d known from the Teton Science School. Rachel was in charge of the Teton Wolverine Project. Gary Lust, the Cessna Pilot, had reported Danny was transmitting the “fatality signal.” When an implanted radio senses no motion for 12 hours it transmits a longer beep. In the case of Danny, the longer beep was coming from bottom of a long steep avalanche path. Rachel wanted to know if it was feasible to retrieve Danny’s carcass — and if so — would I help?

Locating Danny was not dissimilar to an old analog avalanche beacon search. After triangulating his general location we performed a grid search followed by probing and digging, lots of digging. Twenty feet down we found Danny.

Forrest McCarthy and a Scavenged Elk Carcass

Game Creek, Targhee National Forest

Photo by Rob Murray

Photo by Rob Murray

For the next couple winters I occasionally helped with trapping efforts. We ran about a half dozen box traps in the Teton Range. To lure wolverines we baited the traps with road kill, the older and smellier the better. One memorable day I was dragging a rotting moose leg to a trap when I passed some fellow skiers. They asked if I was trolling for grizzlies.

Most of the time when we found the trap closed the culprit was a pine marten. Occasionally we trapped red fox and on one exciting occasion a cougar. All catch and release.

Amy McCarthy and a Juvenile Wolverine

Moose Creek, Jedediah Smith Wilderness

Knowing when you have succeeded in capturing Gulo gulo is easy. When approaching the closed trap you hear a unique primeval growl — the type of growl that causes nightmares. The required visual confirmation, however, is not so easy. While slowly lifting the lid you peer carefully into the dark cavity inside the log box. Inevitably, when just enough light, a set of powerful fanged jaws snap inches from your face. Confirmed: Gulo gulo, the Glutton.

Little is know about wolverine behavior, even less back then. To learn more I was hired full time to track them. I reported to Bob Inman, the Principle Investigator for the Greater Yellowstone Wolverine Program — a partnership of the Wildlife Conservation Society, state game departments in Wyoming, Idaho and Montana and the U.S. Forest Service and National Park Service. Five days a week for two winters I followed and searched for wolverine tracks.

Rob Murray with Telemetry Receiver

House Top Mountain, Jedediah Smith Wilderness

I skied a lot of miles those two winters. I also learned a lot. I learned wolverine den at about 8,000 to 9,000 feet often at the bottom of north facing avalanche slopes where the snow stays cool and downed trees provide subnivean refuge. I learned that male wolverines spend time with kits, even feed with them. I learned that wolverines often scavenge ungulates killed by other predators including cougars and wolves. I also learned a wolverine can cover a lot of ground.

Mother Wolverine at a Natal Den

Spanish Peaks

Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest

One afternoon in mid-February of 2005 Gary Lust located a marked male wolverine on the West Shore of Jenny Lake. Sometime that evening the same wolverine was captured in a box trap at the base of Grand Targhee Resort. Curious, I later followed the wolverines’s tracks. He had gone north from Jenny Lake to Leigh Canyon then west across the Teton Crest to Leigh Creek and Grand Targhee. In roughly twelve hours the wolverine had traveled over twenty miles, across the crest of the Teton Range, in the middle of winter. Badass.

Wolverine Tracks

Jenny Lake, Grand Teton National Park

In 2006, one wolverine went on a long walk-about traveling 250 miles in 19 days making headlines and earning the nickname “The Teton Traveler.” Sadly, the Teton Traveler was fatally captured in a leg trap in Montana’s Centennial Range. In Montana wolverine can be legally harvested.

In 2009 another dispersing male wolverine captured and marked by the Greater Yellowstone Wolverine Project traveled from Wyoming’s Togwotee Pass all the way to White River National Forest in central Colorado. He traveled over 500 miles and crossed two Interstate Highways. Currently the wolverine still resides in Colorado, the first known to do so since 1919.

Mark Packila at the Entrance of a Natal Den

Spanish Peaks

Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest

The future of these amazing mustelids in the lower 48 states is uncertain. To survive, breed and prosper wolverine need big wild spaces with plentiful snow and lots of other critters to eat. Climate change and human development, however, is slowly shrinking these remaining refuges.

In December of 2010, as the of result of the hard work of wolverine advocates including David Gaillard of Defenders of Wildlife, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) determined wolverine in the contiguous United States are warranted but precluded for listing and protection under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). As a candidate species, the wolverine does not currently receive any federal protection. Due to recent developments regarding candidate species, the USFWS is reassessing the wolverine’s listing status. A decision is expected by late 2012.

David Gaillard

May 5, 1967 ~ December 31, 2011

One day while ski-guiding in Grand Teton National Park I crossed a wolverine track. I stopped and explained to my clients wolverine are the largest member of the weasel family and very rare. I pointed out the 3 X 3 Lope, the 30-inch stride and 15-inch straddle. I described thick frost resistant fur, wide five-inch paws, and built in five-point crampons. Bio-engineered for the mountains, I explained, wolverines are the ultimate masters of the winter backcountry.

That night at dinner a waiter asked my clients how was their day of skiing? Never mind the fantastic views of the Tetons and the 3,000 feet of untracked powder — all they could talk about were wolverines.

Produced by

No comments:

Post a Comment